A Dose of Philosophical Pragmatism for Appalachia

Pragmatist philosophy encourages us to evaluate ideas, politics, and cultural practices by their practical impact in our communities rather than according to abstract principles or rigid dogmas.

To bring about a more egalitarian and communitarian Appalachia, we need a clearer sense of what animates the work. Or rather, we must consider what abstractions may be of use in the concrete struggle to create meaningful social change in our ridged region.

Into the orphic realm of philosophy we go.

A Quick Overview of Philosophical Pragmatism

At first blush, it might seem a bit unusual to venture directly into the obscure field of philosophy, but that’s where the roots of Common Appalachian can be found—within philosophical pragmatism, in particular.

Considered America’s unique contribution to philosophy, pragmatism is the wellspring from which this Substack endeavor flows.

Colloquially, “pragmatist” has been co-opted and morphed in popular discourse to serve as shorthand for a person who is willing to do whatever it takes to get what she wants—even if that means jettisoning any sense of principle or higher ideals.

In the philosophical sense, however, pragmatism means something else entirely.

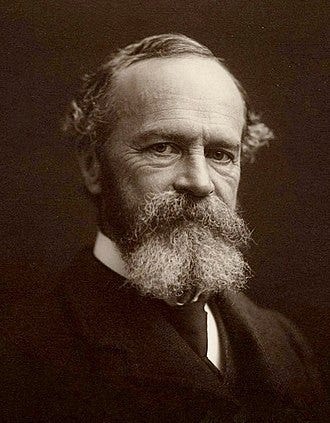

To be a pragmatist is to focus on “fruits over roots,” to paraphrase William James, the nineteenth-century New England philosopher who popularized pragmatism.

For a pragmatist, ideas are evaluated by their practical consequences in our daily lives—the messy, confusing, exhilarating, heartbreaking, inspiring, and emotional fragments that are the most real to us.

Unlike many intellectual traditions—especially in academic or professional philosophy circles—where abstraction-laden scholars focus on the so-called “problems of philosophers,” pragmatists are unrelenting in their focus on the problems and habits of daily life.

I see pragmatism as a philosophy for those eager to neutralize dogmatism, challenge authoritarianism, and foster pluralism throughout Appalachia. Pragmatism has few creeds beyond pursuing what is considered fruitful in our day to day.

(The adjective “fruitful” is deliberately used here to capture the malleability and particularity connected to making value judgments. More on that later.)

To put it crudely, pragmatism is about identifying ideas that work and seeking growth.

What If Truth Is a Constantly Changing Thing?

Change is a constant that means no idea is absolutely true or fundamentally good.

Even so-called “natural laws,” are viewed, by pragmatists, as regularities rather than ironclad cosmic statutes. Truths are, instead, approximations that are fruitful for a time or in a particular place, and are to be discarded when they no longer seem to clarify problems—or when a more potent idea comes along with more thoroughgoing solutions.

Consider an example from Appalachian history.

For decades, the "truth" in forest management was that all forest fires were destructive and needed to be prevented at all costs. This view shaped policy across Appalachia through much of the 20th century. The U.S. Forest Service's fire suppression policy seemed fundamentally true—protect forests by stopping all fires.

They had the evidence: fires destroyed timber resources, threatened communities, and damaged ecosystems.

But this "truth" eventually created problems it couldn't solve. Forests became dangerously overgrown. Fuel built up on forest floors. When fires did occur, they were catastrophic. Meanwhile, some species of plants struggled to reproduce without fire's role in their lifecycle.

A new understanding, however, emerged through studying Indigenous land management practices and observing forest ecology: some fires are not only natural but necessary for forest health. Controlled burns help maintain forest diversity, clear understory vegetation, and prevent larger fires.

What was once considered an absolute truth—all forest fires are bad—has been replaced by a more nuanced understanding that better serves both human communities and forest ecosystems.

This shift illustrates pragmatism in action: the "truth" about forest fires changed when the old idea stopped solving problems and a more effective approach emerged. Neither view is absolutely true for all times and places—rather, each represents a working understanding that helps us manage our relationship with the forest in specific contexts.

The Pragmatist Logic Principle

You may recognize the adage ”By their fruits, ye shall know them” from Christian scripture, but it’s also been referred to as “the pragmatist logic principle.” We evaluate ideas or truth claims based on their fecundity in our lives. (Ah yes, fecund, that is a good word for truth.)

And that requires experimenting upon the word, so to speak.

We learn whether an idea produces good fruits by acting upon it, and observing what practical consequences follow. For a region known for it’s resilience and resourcefulness, this “do what works” mentality feels quite at home.

Truth Isn’t Absolute or Universal

Truthfulness is a quality we apply to something that proves useful in our daily lives. For a pragmatist, a proposition acquires a higher degree of truthiness the more ways and more people for whom it proves useful.

On one end of this spectrum, you may have something like the laws of gravity, which can be applied in nearly universal ways. On the other, there are things like food preferences.

We embrace the laws of gravity, not because they are absolutely true, but because we can do all sorts of practical things when we act as if they are true; build dependable architecture; walk without fearing we’re going to suddenly float into the atmosphere; throw a baseball expecting it to move through the air consistently; dependably travel by railroad; plant seeds anticipating they’ll become seedlings growing upward.

In other words, living becomes quite impossible if you try to do things while disregarding common notions of how gravity behaves.

Your intelligence would be considered incredibly suspect if you were to reject the laws of gravity.

This speaks to the nearly endless number of uses or benefits that the proposition offers people. It’s foundational to so much we do scientifically, socially, and culturally, to say little of its impact on the rest of the organic world.

The laws of gravity are taken as sacrosanct, more or less, by nearly every culture and community. But most truth claims or facts are far less universal.

Pragmatists aren’t trying to find words or concepts that perfectly reflect reality, which is called representationalism. Given the constantly changing nature of reality, pragmatists consider this approach folly.

Instead, pragmatists seek ideas that help us cope with the challenges we experience in our social, political, and natural environments. A representationalist would say something is reliable and useful because it’s true, while a pragmatist might argue that when something is reliable and useful, we consider it to be true.

Another example:

For generations, our mountain farmers planted by the signs—following moon phases and zodiac positions to time their crop cycles. Some might debate whether this system perfectly represents cosmic truth. But what matters is that it works: it's given farmers a reliable framework for planning, created shared wisdom across communities, and produced healthy harvests for centuries. We treat it as true in the sense that it's proven useful, not because it represents some absolute universal law.

Moral ‘Goodness’ Is Particular

The laws of gravity are reliable and useful to all people, but food preferences are a different category entirely.

People are trying to accomplish numerous things with food: acquire daily nutrition, enjoy pleasurable sensations, socialize, communicate ethical values, pass on cultural traditions, participate in economic activity, heal damaged relationships, remedy a medical condition, etc.

So, what is deemed “good” regarding food is wildly varied, depending on individual needs or community values.

A salad with tomatoes and ranch dressing may be good for one person because they enjoy the crunch of fresh greens and cream of dressing and benefit from its nutrients. However, another person may not only dislike the taste of lettuce but may be dairy intolerant and experience digestive challenges from the dressing. Or they may even be deathly allergic to nightshades, which include tomatoes.

What is nutritional and tasty for one person, can be life-threatening to another.

People are trying to accomplish different goals with food in addition to obtaining nutritional value. Bringing a salad to a dinner party when the host asked guests to bring a dessert, or ordering a hamburger at a restaurant when the rest of your tablemates are vegetarian, wouldn’t be considered “good” food choices.

Put another way, the goodness of food is particular and local, meaning we can’t evaluate the ways in which a food is good without taking into account the immediate social context and particular individuals making use of the food.

For a pragmatist, most of what we consider to be true or good falls somewhere between the regularity of natural laws and the particularity of individual food preferences—especially those things that are social or political.

A Healthy Serving of Philosophical Pragmatism

If we are to continue moving toward an Appalachia that values a sense of place, egalitarianism, communitarianism, and pluralism, then there needs to be a healthy dose of philosophical pragmatism animating what we do.

A Sense of Place

According to pragmatism, identity isn’t inherent. For example, there isn’t something unchanging about a person that makes them Appalachian. It’s not in your DNA, so to speak.

For a pragmatist, somebody is Appalachian when they do what Appalachians do. In that same spirit, I’ve previously come up with three mindsets I connect to Appalachian identity.

A commitment to the common well-being of Appalachia that supports the interests of all its inhabitants (human and non-human animal)

A strong affinity for the local, focusing one’s social and political eye toward what’s happening within the geographical territory of Appalachia

A general awareness of and connection to Appalachia’s particular history and cultures that fosters a communal consciousness of the region

So, instead of Appalachian being something you inherit at birth from your parents or the result of where you were raised, Appalachian is an adjective given to those who have a fierce loyalty or strong affinity to the people and cultural practices within Appalachia’s borders.

Biological inheritance and childhood residence are tertiary.

Egalitarianism

Just as pragmatism teaches us that truth emerges from practical experience, true egalitarianism in our region manifests in concrete ways. Every voice in our hollers and communities must carry similar weight in shaping our shared future.

Like those varying food preferences we discussed earlier, equality's expression differs across our diverse mountain landscapes. It shows up when a farmers' market vendor's knowledge about sustainable agriculture guides county policy. We see it in action when a grandmother's understanding of local watersheds influences conservation efforts.

Egalitarianism means dismantling both external power structures that have historically exploited our resources and internal hierarchies that might privilege certain voices over others.

Communitarianism

Think of communitarianism as the gravity that holds our mountain communities together. This isn't abstract theory—it's about neighbors helping neighbors through tough times, like we’ve experienced during post-Helene recovery. It's about local charities and relief efforts.

Like pragmatists who judge ideas by their practical consequences, we evaluate our success by how well we serve our entire community's needs. Our problems don't exist in isolation; neither do our solutions; their ripples touch all of us.

Returning to food: when a community garden flourishes, everyone eats.

Pluralism

Pluralism rejects the idea of a single "authentic" Appalachia. It's that simple.

Like pragmatism's rejection of absolute truths, our version of pluralism celebrates multiple ways of belonging here. Some roots reach back generations. Others are just taking hold. And some people have only recently been grafted onto the tree of Appalachia.

Regardless, all contribute to our region's vitality.

Cherokee wisdom enriches our understanding of these mountains. Enslaved Blacks on the railroads and in mines have shaped our labor consciousness. New immigrant communities, such as the Hmong or Guatemalan, bring fresh perspectives to these ancient hills.

Together, these diverse traditions create something stronger than any single narrative could offer.

Think of it like our mountain forests. A single-species timber stand might look uniform, but it's vulnerable. Our strength lies in diversity. Each unique voice adds another layer of resilience to our shared Appalachian identity.

Ultimately, pragmatists elevate ideas the degree to which they help us to cope with the challenges of existence, individually and as a regional community. Those ideas and cultural practices that don’t are to be cast to the wayside.

Love William James!

A neat crossover: Appalachian Pragmatism. Pragmappalachism maybe?