A Worker-Owned Co-op That Builds Homes in Western North Carolina

Born from an eagerness to explore alternative economic models, Equinox Woodworks has become another beacon for sustainability and egalitarianism in southern Appalachia.

Each brick builds the wall when it comes to broader social change. And that’s exactly what’s happening in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Born from an eagerness to explore alternative economic models, Equinox Woodworks has become another beacon for sustainability and egalitarianism in western North Carolina.

Founded in 2013 by Todd Kindberg, Equinox is a custom home building company in Yancey County that transitioned to a shared ownership business model last year. A resident of Celo, an intentional community outside of Burnsville, Kindberg is no stranger to the cooperative spirit.

Since forming in 1937, Celo has been fertile ground for experimentation with utopian ideals and sustainable lifestyles. For instance, while land in Celo is collectively owned by the community, as part of a land trust, the roughly 70 families living there have personal homes.

In part, Equinox’s transition to a shared ownership model was inspired by Kindberg’s roughly six years at the Arthur Morgan School, a staff-run progressive boarding school in Celo where he experienced firsthand the benefits and rewards of consensus decision-making.

There students are encouraged to “think creatively and work independently and cooperatively, while sharing in a community that honors simplicity, respect, responsibility, and thoughtful consideration,” according to the Quaker-influenced institution’s website.

Recalling Equinox’s origins, Meghan Lundy-Jones, a design team member and financial manager, says Kindberg “had an ethical desire to step outside of mainstream capitalism and explore a different kind of business model.”

Transitioning into a Worker-Owned Co-op

Kindberg found another testament to this harmonious approach in the South Mountain Company, a worker-owned co-op and certified B-corp in Martha’s Vineyard, which helped inspire his vision.

“When he read The Company We Keep by John Abrams,” Lundy-Jones continues, “the then CEO of South Mountain Company, he knew that transitioning to a workers’ cooperative was what he wanted for Equinox in the long-term. Not only were the values of shared ownership and non-exploitative practices a match, but the cooperative business model takes the sole responsibility of business success off the shoulders of a single owner, allowing for a more equal distribution of work.”

In addition to resonating with his democratic temperament, the move fits well with his progression toward retirement.

“As a sole proprietor, this shared work model appealed tremendously as Todd could see that he was on the road to burnout if he didn’t delegate more responsibility,” she explains. “Upon further research, he discovered that owners transitioning into retirement were also choosing to transition to a cooperative model at the end of their tenure because it ensured the long-term sustainability of their businesses.”

This changeover wouldn’t have been possible, however, without the help of the Industrial Commons (TIC), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that scales social enterprises and assists businesses in becoming worker-owned cooperatives. Kindberg met with TIC Co-Executive Director Molly Hemstreet in 2019 to discuss the nuts and bolts that this refreshing development would require.

A few years after their “serendipitous meeting,” Equinox completed the conversion to a worker-owned cooperative in spring 2023. TIC’s Senior Director of Workplace Development Aaron Dawson and Rob Brown of Cooperative Development Institute provided further support, reviewing bylaws and operational agreements.

“Even if it is a bit in the distance, the sooner you plan for an exit strategy, the more likely you will be able to plan to get what you need, as an individual or as a business,” Dawson explains. “Whether you are thinking of passing the company on to other family members, selling through a broker, or selling to your employees, which is a great option that people often overlook, we help you think through the options.”

A Worker-Owned Co-Op Approach to Building Homes

In this flattened business structure, not all employees at Equinox are owners, however, but rather everyone has the opportunity to share ownership once they meet certain criteria, including two years of employment and a minimum of 2,500 hours worked.

Additional requirements entail an intention to work at Equinox for the foreseeable future. This isn’t an absolute commitment for a set number of years, but the expectation of long-term employment. Worker-owners must showcase their ability to work well and cooperatively in whatever position they hold and make Equinox their primary employment.

After all, the right culture fit is foundational to the success of a worker-owned enterprise, which can take time to properly assess.

To nurture this, worker-owners must “demonstrate exemplary work and cooperation, or steady improvement where necessary, a non-defensive attitude that encourages constructive criticism from others, and a reflective attitude that permits self-criticism,” Lundy-Jones explains, and they must embody “a commitment to understanding and honoring the issues that are central to the company’s values: quality work, ethical business conduct, environmental responsibility, and concern for other people.”

It’s a rather extensive vetting process throughout those two years, with employees being continuously evaluated for ownership suitability and educated about the meaning of shared ownership.

“The expectation is that it will be clear,” she continues, “when each employee reaches eligibility, whether the employee is ready to accept the responsibility and whether the current owners are ready to accept the employee as a new owner.”

Before becoming full worker-owners, employees also have to pay an ownership fee of $5000, which can be spread out in payments over their first three years as a shared owner. The new owner takes on all responsibilities and receives all benefits of ownership once 50% of the fee has been paid.

A Philosophy of Human-Centered Design

Its hierarchy-skeptical approach to construction isn’t the only thing that makes Equinox stand out, however. The team is also deliberate in articulating the philosophy that informs its sustainable and ecologically responsible methods.

For this, Equinox draws heavy inspiration from Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language and Sarah Susanka’s The Not So Big House.

Alexander's A Pattern Language challenges conventional design by proposing a bottom-up approach using 253 interconnected patterns. These patterns, each addressing a specific human need in the built environment, range from small-scale details like window placement to larger concerns like neighborhood layout.

In essence, the book empowers individuals to build and shape their surroundings based on principles Alexander's acolytes consider timeless—community, livability, and a deep connection to place, to name a few. While not without its critics, A Pattern Language remains a seminal text, inspiring architects, designers, and everyday people to create built environments that resonate with their human values in relation to the natural world.

In kinship with Alexander’s work, Sarah Susanka's The Not So Big House sparks a design revolution urging homeowners to prioritize quality over quantity.

She argues that happiness doesn't reside in square footage, but in thoughtfully designed spaces that align with how we truly live. By emphasizing function, flexibility, and meaningful connections to the outdoors, Susanka encourages readers to build smaller, yet richer homes that feel spacious, and comfortable, and reflect their unique needs and values. Her manifesto critiques McMansion-style living, inviting others toward mindful and sustainable home design that nurtures both our material and spiritual needs.

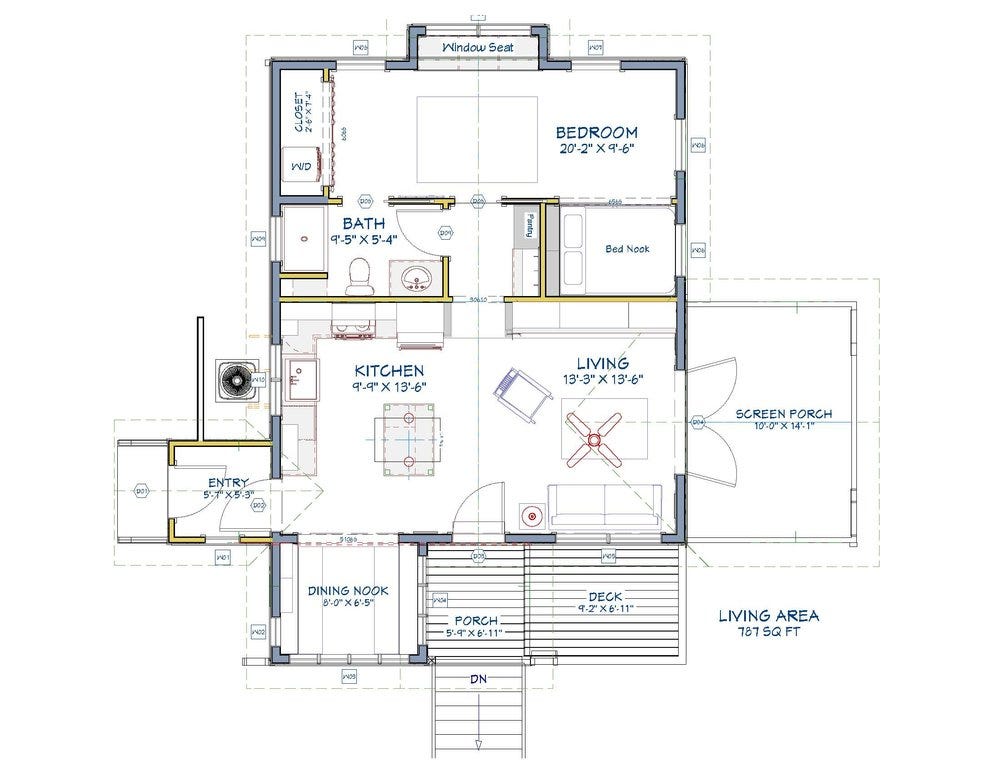

When asked how their approach contrasts with contemporary building methods, Lundy-Jones remarks, “Most ‘mainstream’ construction is about quantity over quality, and the average homes being built today in America are not built to last. We prioritize small footprints and creative ways to make use of small spaces, which has been influenced by Sarah Susanka’s work. We also work with clients to build a home that is custom built and Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language helps us facilitate that kind of design work.”

The Pretty Good House and Builders for Climate Action are two other like-minded sources whose perspectives she says also really “jive” with the Equinox team, as well.

Constructing an ‘Appalachian Vernacular’

In reviewing their collection of completed construction projects, both commercial and residential, it’s easy to see how important genuine community and livability are to Equinox—to varying degrees a refutation of the urban design and residential construction patterns that became ubiquitous after World War II.

When it comes to living well and designing a physical environment that enables families and neighborhoods to flourish, several things remain front of mind for these eco-conscious builders and designers.

“We’ve built several homes for the folks at High Cove Community in Bakersville and they have some great guidelines for building in relationship to community,” Lundy-Jones says. “One element that’s important to them is for each house to have an inviting entryway so neighbors feel welcomed.”

This stands in stark contrast with most homes built in the past half-century “plac[ing] their garages front and center,” symptomatic of a car-centric cultural bias detrimental to community-making, social capital generation, and the environment.

(Notably, the pending return of passenger rail to western North Carolina would add further steam to this more human-centered approach to home and neighborhood design.)

Equinox wants to foster a genuine sense of place that’s increasingly lost to mass culture.

“It’s also important to us to consider how a home fits into the landscape and the culture of our community aesthetically,” she continues. “We are talking a lot these days about ‘Appalachian vernacular’ and how that should influence designs so that our homes blend in with the landscape, rather than the norm which can sometimes make a house stick out of the landscape like a sore thumb.”

Equinox constructions are also NC Green Built Homes, meaning, builders and clients make design choices that take operational carbon usage and carbon embodiment into account. They strive to achieve the highest certification level possible while keeping projects affordable for clients.

Advice for Others Wanting to Become Worker-Owned Co-ops

For those also considering the shift toward a shared ownership model, it’s best to build upon the foundation of others rather than expend energy and resources drafting an entirely new blueprint.

“Find models of other businesses like yours that have done this already and ask them to share their process and documents,” recommends Lundy-Jones. “We would not have been so successful at creating our documents without the full transparency of South Mountain Company. Working with Rob and Aaron was also crucial for us to develop a timeline and stay on target with our goals. Understanding the value of our business before selling it to the workers’ co-op was also a critical first step.”

One great hope is that each newly minted worker-owned co-op will generate additional momentum for more democratic business models in Appalachia.

And Equinox remains optimistic.

“We have friends who own a coffee shop nearby that have reached out to Industrial Commons to see what the next steps for them might be,” she says. “They have thought about this business model for a while, so seeing us engage in the transition was exciting to them.”

I wonder what might be considered as part of "Appalachian vernacular." Asheville has pebbledash, which is relatively unique to the region. At least in Buncombe.

Would love to have them build a home for me if we end up getting land nearby for a new home.