How Economically Distressed Is Appalachia in 2023?

Appalachia has made economic progress since 1965, but 82 of its 423 counties remain "distressed," per a June 2023 report by the Appalachian Regional Commission.

BURKE COUNTY, NC—One of the more formal demarcations of what qualifies as Appalachia stems from boundaries outlined by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). Founded in 1965, ARC was created as an economic development partnership between 13 states and the federal government.

ARC now consists of 423 counties (that should be flying the Appalachian flag), adding three new counties in November of 2021 (including Catawba and Cleveland, located directly east and south, respectively, of Burke County).

By many measures, ARC’s success has ranged somewhere between mixed and slightly positive in reducing poverty, increasing incomes, improving health, and expanding infrastructure in Appalachia, according to a study commissioned by ARC in 2015.

For instance, the number of high-poverty counties in Appalachia decreased from 295 in 1960 to 170 between 2008 and 2012. And infant mortality rates dropped by more than two-thirds in Appalachia.

On the other hand, per capita income levels were reported at 75 percent below the U.S. average. Plus, the percentage of the region’s population age 25+ with a bachelor’s degree or higher remains below the U.S. average.

A June 2023 report by ARC updates the picture in Appalachia.

So, What Is Considered Appalachia?

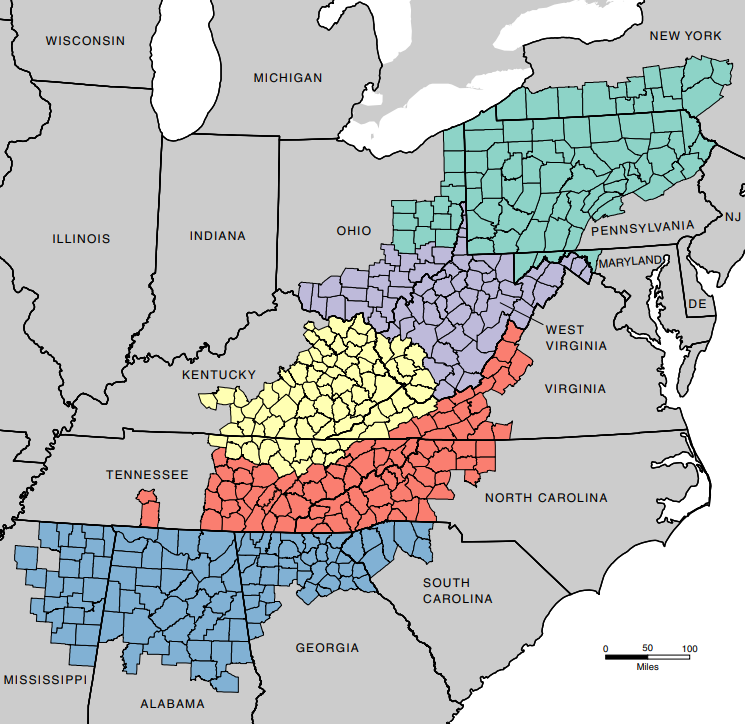

To accomplish better analytical detail, and, hopefully, more effectively serve our mountain region’s economic interests, ARC subdivides Appalachia into 5 smaller areas:

South (Mississippi, Alabama, George, and South Carolina)

South-Central (mostly Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia)

Central (mostly Kentucky, with bits of its neighboring states)

North-Central (most of West Virginia, and southern Ohio)

North (Pennsylvania, New York, and a jag of eastern Ohio)

Admittedly, when I refer to Southern Appalachia, I primarily have ARC’s South-Central subregion in mind. But that’s largely because broadening my framing beyond those boundaries begins to feel unruly and abstract.

In a few words, less local and less embodied. It begins stretching the capacity of human-scale to its limits.

Concerns of framing and boundaries aside, what is Appalachia’s economic health look like in 2023?

Appalachia’s Economic Health in 2023

By many accounts, Appalachia has continued to see economic development improve since the 2015 study, and definitely, since ARC’s inception when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Appalachian Regional Development Act into law in 1965.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing housing affordability crisis, divestment from coal, and the persistent opioid tragedy have acutely impacted life in Appalachia, derailing some of these efforts.

To compare the economic performance of each county in our region with the national averages, ARC uses a system that assigns an index score based on three indicators: three-year average unemployment rates, per capita market income, and poverty rates.

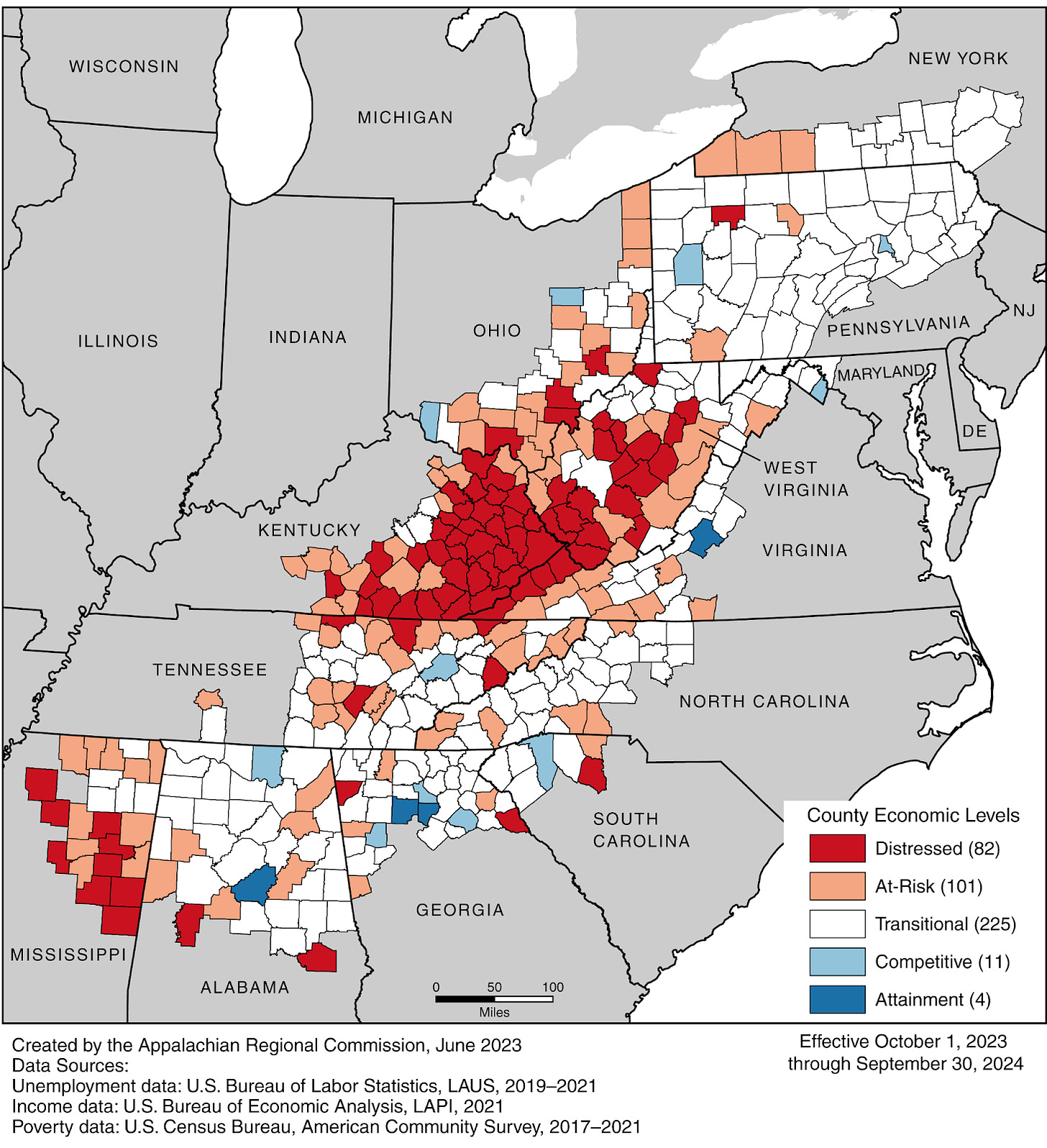

Based on these scores, each of the 423 counties in Appalachia falls into one of five categories of economic status—distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive, or attainment. These categories also help determine how much matching funds are required for ARC grants, as well as what research topics and investment strategies are most relevant for addressing the needs of the Region’s most disadvantaged areas.

Now, in what economic state does that leave our mountain region presently?

The economic status of the counties in the fiscal year 2024 is based on the following breakdown: 82 distressed, 101 at-risk, 225 transitional, 11 competitive, and 4 attainment. This analysis also uses historical data, shows changes over time, and guides ARC’s grant allocation process.

It also begins to capture the economic effects of the COVID crisis as more recent data are now accessible.

What News for Burke County and the Foothills?

Most of western North Carolina finds itself in either the “at-risk” or “transitional” designation. Yes, even comparatively wealthier counties such as Buncombe, Henderson, and Catawba have been identified as transitional.

In more detail, here’s how Appalachian counties in North Carolina breakdown:

Transitional: Alexander, Ashe, Avery, Buncombe, Burke, Caldwell, Catawba, Clay, Davie, Forsyth, Haywood, Henderson, Macon, Madison, Mcdowell, Mitchell, Polk, Stokes, Surrey, Swain, Transylvania, Watauga, Wilkes, Yadkin, Yancey

Distressed: Cherokee, Cleveland, Graham, Jackson, Rutherford

Burke has specifically received a “transitional” label for 2024 because 50% of the county’s maximum ARC share for projects are currently funded, including 2 “distressed areas.”

You can toggle around an interactive map on ARC’s website, while below is a static version.

A Few Reactions to the 2023 Economic Distress ARC Report

In response to ARC sharing this report on its LinkedIn page on June 27th, several folks left their own reactions.

ARC’s Effectiveness Is Doubted

Tee Faircloth, CEO and founder of Coordinated Care Inc., a group dedicated to the economic transformation of rural communities, not only brought into question whether the ARC has had a meaningful impact, but if it focuses enough on the most economically marginalized in our region.

“So, how would this have looked before the ARC? Seems like little has relatively changed for the poor in Appalachia over the 58 years,” he said. “The ARC was founded to serve primarily what is Central Appalachia. The rest were largely added for political concerns. Those have thrived.”

He cast further doubt on whether certain municipalities should even be considered part of Appalachia, highlighting the oft-quoted cultural and economic divides between urban and rural communities.

“Central Appalachia is poorer, while the three largest beneficiaries of ARC largesse have been: 1) Lexington, KY, 2) Pittsburgh, PA, and 3) Chattanooga, TN” he explains. “Lexington— not even in Appalachia. Pittsburgh—home of the Carnegies and Mellons. Chattanooga—highest percentage of inherited wealth in the country.”

Appalachia’s Most Forgotten Subregion

Drawing additional attention to the plight of West Virginians, James McCormick, a retired Army Captain who leads Vets4Energy, described the report as “a clear indicator that we have a long way to go to get West Virginia off the ropes and back on the mat slugging it out.”

“Appalachian-friendly agriculture is one area that could help move the needle,” he continued, “however, recent statistics from USDA Census shows a loss of 15 farm operations per month since 2017. Perhaps this is an area with potential for those impoverished counties?”

Amy Weislogel, an associate professor of geology at West Virginia University (WVU), continued the lament for the Mountain State.

“I fear Monongalia Co. WV is about to decline as WVU goes through its contraction, unfortunately,” she said. “Will undoubtedly have ripple effects in other WV counties, as well.”

Replying to another comment with regards to new economic models, Weislogel argued, “There is so much going on in the basin around the energy transition that’s centered around geoscience— geothermal, critical elements, underground nuclear salt reactors—not to mention the increased flooding in WV as precipitation patterns change.”

She believes much of the economic life of hinges on WVU.

“All of these involve huge challenges and yet because our university is deep in debt we can’t make hires or retain faculty so we have fewer advisors and we can’t teach certain classes and so have fewer teaching assistantships available,” she explained. “So students are missing out on the training needed to enter career paths in these new economic sectors, which means there will have to be a workforce brought in from out of state and that is just salt in the wound for WV.”

However, West Virginia isn’t the only place some feel has been neglected by ARC.

Sheryl Davis, founder and principal of the American Music Landmarks Project, an organization connecting people to places that have shaped popular music history in the U.S., drew attention elsewhere.

“As usual, Athens County, Ohio remains distressed and forgotten,” she observed. “What will it take for this area and the people to have access to opportunities and support to turn despair into hope? This especially pertains to the county's residents who do not live in the City of Athens but rather places like the village of Trimble.”

She further mentioned her own struggles to revitalize community.

“I'm applying for funding through the $500 million Appalachian Community Grant Program in an effort to acquire the resources necessary to rehabilitate two historic buildings as economic revitalization tools,” she said. “This grant could very well be the one and only chance the village of Trimble will ever get to change its long-held trajectory of devastation.”

‘We can’t sustain it alone.’

No doubt some feel the unequal ways in which economic support has been distributed by ARC throughout Appalachia. However, some believe ARC’s focus on “distressed” counties means those in slightly better circumstances or are not given the resources they need to fully turn the corner.

“I can't complain about focusing efforts on helping distressed areas,” says Shane Farthing, Director of Economic and Community Development in Martinsburg, West Virginia. “But I fear over-emphasis on this step fails to help ‘transitional’ places successfully transition. If ARC undertakes an effort to specifically help these communities, I would love to be involved.”

I believe many folks in Burke County, specifically Morganton, feel similarly. For years Burke residents have bandied about similar notions about Morganton’s economic prospects. My hope is that Morganton can be ground zero for egalitarian-minded economic development.

“As it stands, we now seem invisible to ARC because we've started some successful things to get out of the distressed category,” he continues. “But we can't sustain it alone.”